Imagining what could be.

Sometimes the critical constraining resource is what you can and can’t imagine. In 2011 Google Foundation gave us a large un-solicited grant to recreate an HTML5 version of our Java program Molecular Workbench. I desperately wanted to shift what people imagined was possible.

The story starts here

For many years I worked with Bob Tinker. I first worked for Bob at TERC where we created and implemented the idea of probeware – connecting sensors and interfaces to microcomputers to support real-time collection and display of sensor data for science education. In 1995 we started Concord Consortium together. We could easily imagine things that didn’t exist and then iteratively improve and evolve our ideas and designs all in our imagination before we started implemented them.

I worked closely with Bob for a long time and it was only later that I realized that collaboratively designing things in our imaginations was unusual and this wasn’t something that everybody did.

An unusual opportunity.

In November 2011 I was working as the Director of Technology at the Concord Consortium, a non-profit tax-exempt research and development organization focused on develping and adapting technology for science and math learning and the Google Foundation gave us a grant to develop an HTML5 version of Molecular Workbench. Molecular Workbench is an open-source, award-winning Java-based 2-D physics simulation system created and developed at Concord Consortium by Charles Xie.

We looked at several different approaches to acomplishing this and everybody was quite skeptical that JavaScript in browsers would be fast enough to implement a real-time interactive 2-D molecular simulation. One of the approaches being considered was some kind of Java to JavaScript re-compilation approach.

I suspected that if we rewrote it from scratch with performance in mind that JavaScript would be fast enough. The problem would be getting buy-in from the team.

Earlier examples of fast JavaScript computational models.

Earlier in 2011 I converted two existing computational models with dynamic visualizations written in Java and NetLogo into JavaScript and knew that when implemented appropriately performance in browsers was much faster than people realized.

Energy2D in JavaScript

At Concord Consortium Charles Xie had also created a Java-based modeling system for 2D thermodynamics modeling called Energy2D. Energy2D models three modes of heat transmission: conduction, convection and a simple model of radiation.

In June 2011 I spent a week converting the Java version of Energy2D into JavaScript. I was curious how painfully slow the JavaScript version would be.

Avalanche2D in JavaScript

Later in 2011 just a month before we got the grant from the Google Foundation I had written a relatively simple computational model in JavaScript called Avalanche2D-JS that simulated self-organized criticality, an area of physics that can model when an avalanche is most likely to occur in systems like a pile of sand getting steeper as sand is slowly added.

The model had originally been written in NetLogo by Bob Tinker and the original NetLogo version ran about 22 model steps per second. Seth Tisue the lead developer of NetLogo rewrote Bob’s model and Seth’s faster version ran about 520 model steps per second.

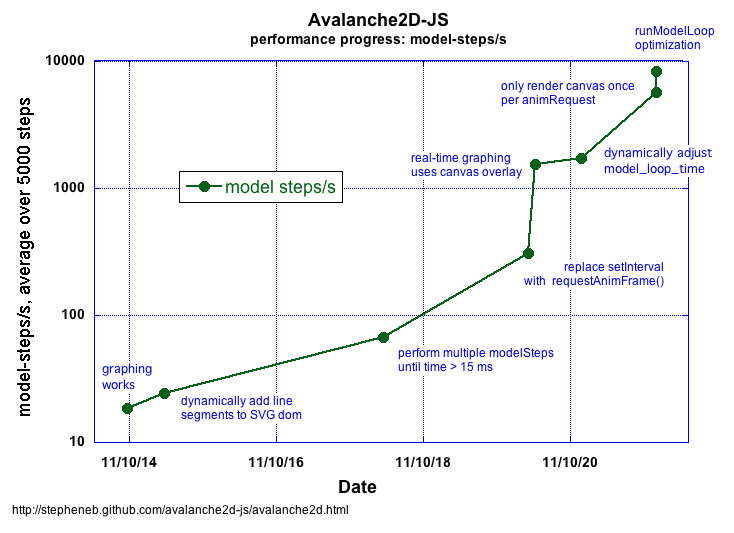

My initial JavaScript implementation started reasonably fast at about 50 model steps per second however over the next 11 days I improved the performance by a factor of 50 to almost 10,000 steps per second.

You can run annotated versions of Avalanche2D-JS at eight different points in its development here: JavaScript computational model and visualization: 50x performance improvement

Data I collected on performance improvement during the initial development sprint in 2011. I’ve never had the chance to use a log scale on the Y axis in a performance graph like this before!

Should we rewrite Molecular Workbench from scratch in JavaScript?

At this point I knew that JavaScript had the computational performance for all kinds of modeling but was surprised when I had trouble getting folks to buy in to this approach.

I think there were three aspects to their concerns:

- Developers on the team and other management still thought of JavaScript in the browser as relatively slow.

- The Java version of Molecular Workbench has a very extensive set of features, authorability, and extensibility and in the beginning of the grant it wasn’t clear how many of these features we would need to implement in the browser to be successful.

- Most of our resources came from NSF grants. This was only the second large grant from a foundation and our first from the Google Foundation. I think the perceived risk of not using the resources in the grant from the Google Foundation effectively made people more conservative in what they could imagine.

I perceived the risk quite differently.

I wanted to create a more general framework for computational and visual modeling in order to inspire innovation and collaboration between projects and groups.

At that time almost all of funding for Concord Consortium came as science education research grants from the National Science Foundation. We never got grants directly for the development of technology instead technology developed in a project supported the research goals. As much as I could I encouraged development of technology in one project to build on development in earlier projects and contribute to new projects. This wasn’t as easy as it might have been if our funding wasn’t based on research grants. In order to get a research grant you need to propose something profoundly new that has a reasonable chance of being successful and providing great value. Often that also meant developing prototypes of new technology as quickly as possible without the funding for generalization.

The Google Foundation grant was the first we ever received which was specifically for development of technology and I wanted to use these resources to develop a shared technology that encouraged more synergy between our projects and between us and similar groups.

I suspected this opportunity would not come again and was most worried about ending up with a modeling system that could only be used for a small set of 2D molecular models and on just a few projects.

In order to convince the team about the performance aspect I decided to build the simplest real-time interactive molecular model in JavaScript and do this as quickly as I could.

A fast and simple molecular simulation in JavaScript

In early November 2011 I posted this gist: Simple Molecules which implemented a 2-D molecular model using a simple model of neutral molecules interacting with each other via Lennard-Jones potential forces.

Simple Molecules

While the model is running you can interactively change:

- Number of molecules.

- Temperature of the system.

- Lennard-Jones potential force coefficients.

Click the Go button to start the model.

The Lennard-Jones potential force model implements an an attractive force between molecules that is at a maximum when two molecules are close to each other. When two molecules get even closer to each other the force becomes repulsive and increases very quickly as the distance shrinks.

- The coefficient for the attractive force is called epsilon. Epsilon specifies the depth of the potential well between each pair of molecules. Epsilon can be changed by dragging the circular handle at the bottom of the valley in the graph up or down.

- The coefficient for the distance at which the force changes from attractive to repulsive is called sigma. Sigma specifies a finite distance at which the inter-particle potential is zero. Sigma can be changed by dragging the circular handle pinned to the X-axis on the graph left or right

At each step of the model a new acceleration is calculated for every molecule by summing the Lennard-Jones potential forces between each pair of molecules in the system. The new values for accelerations are then used to update the velocities of each molecule. A much simpler collision physics is used when molecules bounce off the container walls.

As far as I know this is the very first JavaScript 2-D molecular simulation which implemented both a computational engine calculating inter-molecular forces and kinematics along with a dynamic visualization of the molecular kinematics.

The Lab framework

Two years later we had created an entire framework for modeling and visualization we called The Lab Framework.

Charged and Neutral Atoms (conceptual version).

Here’s one of the simpler models. In this model you can increase or decrease temperature and the van der Waals attractive force which is another name for the attractive element of the Lennard-Jones potential forces. You can also add an electrical charge to the atoms which adds a second force calculation to the model.

Click the Play button in the controller at the bottom to start the model. Make the temperature low enough and the van der Waals attractive forces will cause the atoms to start freezing into a hexagonal lattice. Try turning on Charge and note the change in the lattice form.

Comparing deformation caused by forces applied to rubber, metal, and ceramic

We created a utility to import existing XML-based Molecular Workbench interactives and convert them into the JSON form used by the Lab framework. Here are three examples showing different ways forces deform rubber, metal, and ceramic-like materials.

Rubber deformation

Rubber will bend with an applied force and spring back when the force is removed.

Start the model and try adding and then removing different forces.

Metal deformation

Metal will deform under a force and spring back unless the force exceeds the elastic limit of the material. Force beyond this limit cause a ductile deformation.

Start the model and try adding and then removing different forces.

Ceramic deformation

Ceramic will deform under a force and spring back until the force exceeds the elastic limit at which point a fracture will occur without ductile deformation.

Start the model and try adding and then removing different forces. If you add a large force pay attention to how the ceramic material fractures.

Pendulum Experiment

The same molecular modeling engine can also be used to simulate a simpler system of forces and kinematics such as those in a pendulum.

In this example the interactive has been extended to support collecting multiple trials investigating how the initial conditions, rod length, mass of the ball, and starting angle affect the period of the pendulum. The results of each test are saved and displayed in the experiment table and and X-Y parameter graph.

Choose your initial conditions and click the Start button. Save the results and then click Next Run. Click the ? control in the upper left to see the embedded help for this interactive.

Interactive definition and authoring.

Lab framework Interactives are defined with a JSON structure for the Interactive and a second JSON structure defining the initial condition for the model.

JSON structure for the Interactive: Charged and Neutral Atoms (conceptual version).

The Interactive JSON includes a models array where one or more models can be referenced. In this simple interactive just one md2d model is defined which has a url property that refers to the JSON structure defining the initial condition of the molecular model.

"models": [

{

"type": "md2d",

"id": "100-atoms-charged",

"url": "models-converted/lab-version/1/md2d/conversion-and-physics-examples/100-atoms$0.json",

"viewOptions": {

"controlButtons": "play_reset"

}

}

]

JSON structure defining the initial condition of the molecular model: