Intonation for small high-performance guitars.

I’ve recently finished two small high-performance steel-string guitars inspired by the 1918 Martin 1-18 plans Ted Nelson created for GAL. There are some interesting intonation issues I am investigating that I suspect are inherently more difficult to ameliorate because the tops have been designed to work very efficiently with lightweight steel strings.

Two guitars finished November 2018

By “finished” I mean in the last couple of weeks I’ve finally got the bridges glued on and have done some initial work on action and intonation. The guitars of course are still changing slowly and settling in.

I’m very happy with the guitar with the White Pine top.

John Fabel, my guitar-building mentor playing my one day old guitar with the Sitka Spruce top. I built this one for my daughter. She hasn’t played much so I set it up with extra-light Silk and Steel strings.

I had just glued the bridge on this guitar one day before taking this video so the guitar is still changing all the time and needs more work on action and intonation.

I created these two guitars over a four year period meeting once a week with small group of folks all building similar guitars inspired by the 1918 Martin 1-18 plans. We were mentored by John Fabel who has experience building and repairing guitars and violins. I was also inspired by Trevor Gore’s work and book: Contemporary Acoustic Guitar Design and Build.

Intonation issues with small, lightweight, highly responsive tops

Both guitars have extremely responsive tops that can be easily driven with light strings, are impressively loud and have long sustains.

I setup the neck, saddle, and nut on both guitars for a reasonably low action and on the White Pine guitar added some initial offsets to the saddle and nut for intonation.

I then tap-testing and collected frequency response data for the front and back with the sound hole plugged and again for the top with the sound hole open. This gave me values for the following resonances:

- Helmholtz: about 115 Hz. The resonance associated with the interior volume and the size of the sound hole.

- Main top monopole, T(1,1)2: about 200 Hz with the sound hole plugged and 212 with the sound hole open. This is the large resonance associated with the top panel in the lower bout.

- Main back resonance: about 290 Hz with the sound hole plugged.

I also recorded the pitch of all the scale tones up to the 12th fret to better understand what lind of intonation issues I was dealing with.

On the White Pine guitar I also included the ability to add masses of different weights to the interior sides of the lower bout. I collected the data described above without any additional side mass weights and then with the maximum of an additional 300 grams attached on each side. I created sets of weights from 50 to 300 grams in increments of 50 grams and plan to collect data using all the intermediate side mass weights in the future.

With an additional 600 grams of mass attached to the sides the T(1,1)2 resonance dropped about 7 Hz with the sound hole plugged and about 11 Hz with the sound hole open. The Helmholtz resonance dropped about 1 Hz and the back dropped about 12 Hz.

I was surprised at how much the Helmholtz and T(1,1)2 resonances affected the intonation in the scale tones. Multiple scale tones below a resonance were flattened while those above were sharpened.

While I can certainly still improve the intonation the large effect of the scale tones coupling with the existing resonances will make it difficult to get the intonation I hoped for.

Reflecting on this intonation issue I suspect the coupling of scale tones with resonances is probably inherently more pronounced when a top is very light and responsive and designed to work well with the smaller amounts of energy available in light and very light strings.

A couple of steps I plan to try first to lessen the intonation errors before working on correcting them by making further changes in nut and saddle offsets.

- Lower the fret height. I used EVO gold FW43080 fret wire and with the light and extra-light strings I designed these for I don’t need all 0.043” of the fret height. While examining the intonation errors in the first few frets on E2 I noticed I didn’t need to press as hard as I normally do to get a solid stop on the fret and that pressing harder increased the sharpness of the intonation error.

- Double check the neck relief using the appropriate strings for each guitar and use the truss rod to set it to 0.1 mm.

- Lower the action.

After I’m satisfied with these steps finish making changes to saddle and nut offsets to correct intonation over the scale tones I care most about as much as is practical.

Tap testing and initial intonation measurements: White Pine top

I collected frequency response data from the top and back with the strings tuned and then muted and the sound hole plugged with a small section of a rigid foam cone. I also collected data from the top with the sound hole open.

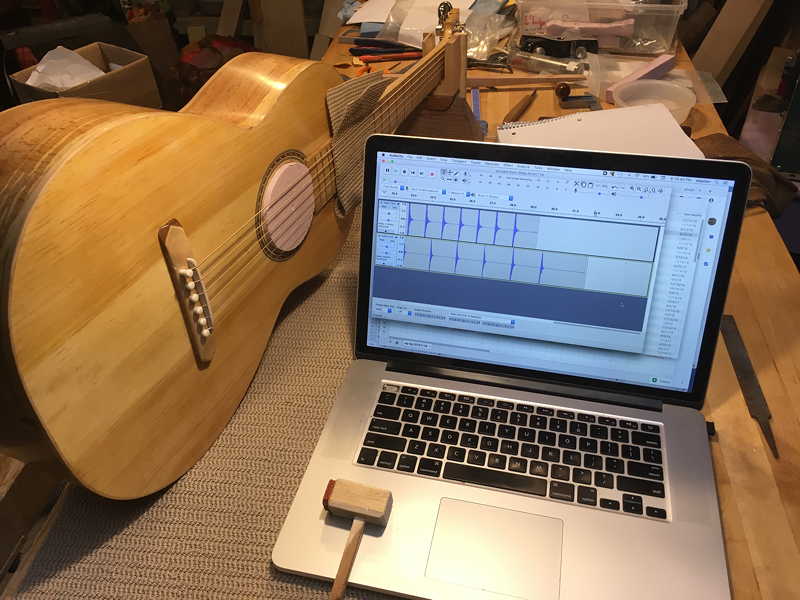

Collecting spectral response data with Audacity.

Main resonances with no additional side masses

Initially without adding side mass weights the main monopole T(1,1)2 resonance in the lower bout is about 200.2 Hz. The tapping was located in the center of the lower bout just tail side of bridge.

These data are collected with the sound hole plugged (and strings muted) so the Helmholtz resonance both doesn’t show up and the coupling effect which increases the T(1,1)2 resonance by almost 13 Hz isn’t present either.

The same test with the sound hole open shows the Helmholtz resonance at 115 Hz coupling with the T(1,1)2 resonance increasing it to almost 213 Hz.

The back has a resonance of about 293 Hz with the sound hole plugged. This can be easily reduced if needed by taking small amounts off the tops of the lower radial braces and from the center scooped section of the cross brace.

Intonation errors with no additional side masses

With the top so lightweight and efficient the main resonances in the top and back and the air resonance associated with the enclosed volume have enough power to shift the pitch measured when individual scale notes are fretted and played.

I don’t actually know whether the frequency of the string itself is being shifted or perhaps just active panel sections of the guitar. Might be interesting to also measure the string frequencies with magnetic pickups.

Here’s a graph showing the intonation errors (in cents) for the scale tones for all the strings up through fret 12 for the White Pine guitar without any additional side masses. Each string is a different color.

Here’s the table of the intonation errors (in cents) for the scale tones for all the strings up through fret 12 for the White Pine guitar without any additional side masses.

Main resonances with two added 300 gram side mass weights

Adding two 300 gram side mass weights lowered the main monopole T(1,1)2 resonance in the lower bout about 7 Hz to 193.4 Hz.

Same test with sound hole open shows the Helmholtz has dropped about 1 Hz to 114 Hz and the coupled T(1,1)2 resonance has dropped about 12 Hz to 201 Hz.

The back resonance has dropped about 11 Hz to 282 Hz with the addition of the two 300 gram side mass weights.

Intonation errors with two 300 gram side masses added

Here’s a table showing the intonation errors (in cents) for the scale tones for all the strings up through fret 12 for the White Pine guitar with the two added 300 gram side mass weights attached. Overall many of the intonation errors have been reduced somewhat compared to the measurements with no side weight masses attached.

Here’s a graph of the same data. Each string is a different color.

I regenerated the same intonation data this time using the lightest fretting pressure possible to get a clear note. This chart shows that while many of the intonation errors are less there are still similar patterns of errors.

I did one more collection of intonation data however this time I worked to mute the resonances in the top lower bout by covering it with a rubbery friction fabric and piling 2300 grams of unused side mass weights on top.

The T(1,1)2 resonance and presumably many more were reduced but not eliminated.

I was especially interested in seeing what strings 6, 5, and 4 looked like around the T(1,1)2 resonance.

The T(1,1)2 resonance and presumably many more were reduced but not eliminated. The large flattening below 210 Hz and sharpening above have been reduced.

I am quite surprised that the intonation errors in string 6 around 110 Hz seem to have almost disappeared.

Here’s a picture of what I did to partially mute the top. John Fabel suggested also trying to mute the bridge where the pins are located. Another variation I will try.

Maybe an octave harmonic of the T(1,1)2 is causing the problem.

Trevor Gore suggested part of the problem could be an artifact of the tuner responding to a resonance of 430 Hz – a low-order harmonic of 215 Hz.

With the two 300 gram weights attached to the sides and the sound hole open I measured the T(1,1)2 resonance at 201.2 Hz … so perhaps I should be looking for resonances closer to 400 Hz also??

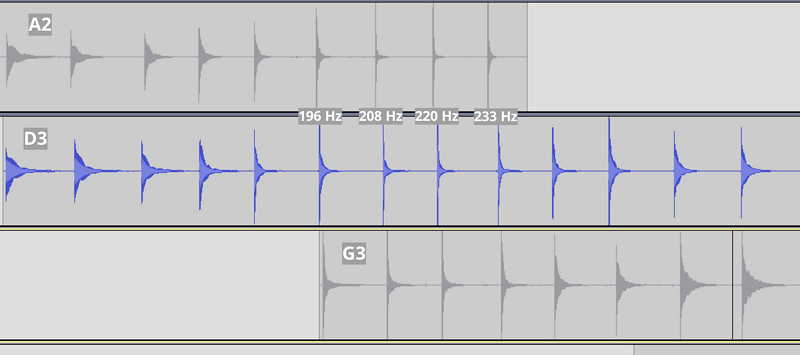

I re-collected all the scale tone intonation errors by collecting audio samples of each scale tone in Audacity. I actually had to do this twice, once at 8000 Hz to get high-resolution spectral data and again at 22050 Hz to get better resolution data for the pitch detect plugin to process.

I then selected each sample and used my extended version of the Pitch Detect plugin which allows me to additionally specify an offset time to start sampling. My settings were a 0.25 s offset followed by an 0.5 s sampling period.

E2:4 is measured almost 12 cents sharp using the Audacity pitch detect plugin – and looking at the frequency data I can see there is a harmonic right around 415 Hz (418 Hz).

A2:12 is another scale tone that is almost 9 cents sharp. The frequency data does not show a harmonic around 415 Hz, instead it is 439 Hz.

A2:11 which appears to be only about 1 cent sharp does have a harmonic at 416 Hz.

D3:12 which should be scale tone D4 at 293.7 Hz is 12 cents flat at 292.6 Hz. The first obvious harmonic is at 587 Hz which doesn’t seem like it would contribute to T(1,1)2 but the next harmonic at 880 might if it had enough energy.

And of course B3:9, which is G#4 at 415.3 Hz is being pushed about 9 cents flat.

Note: I collected these data without muting the other strings

UpdateL 2018 11 24: 200 gram mass weights, Chladni patterns

I made a few changes and collected more intonation data and tried to force some visible Chladni patterns on the top.

- Reduced the side mass weights from 300 to 200 grams.

- Took 0.1 mm off of frets (about 1.15 to 1.05 mm) and re-crowned.

- Lowered nut 0.1 mm.

- Lowered saddle 0.2 mm.

Changes in measurement procedure:

- Collecting 12 scale tones and the 12th fret harmonic with Audacity and later generating pitches using Pitch Detect plugin,

- Now muting other strings during collection.

Now the maximum flat intonation error is visible on the 5 and 4 stings and is deepest around 185 Hz.

I put a loudspeaker over the sound hole (strings under tension and tuned), sprinkled black tea leaves and swept through a range of frequencies looking for resonance patterns. Didn’t get very many but there was a strong resonant responses at 353, 366, and 369 Hz which is just about exactly twice the deepest intonation flattening at 185 Hz … hmmm.

Chladni patterns from White Pine top with strings tensioned and tuned (20181124).

Frequency response of White Pine top, 200 grams side mass weights.

There are peaks at 115.2, 152.3, 190.4, 205.1, 208.0, 240.2, 254.9, 306.6, 376.0, 441.4, and 528.3 Hz.

An interesting aspect of collecting the intonation data in Audacity is that it’s very easy to correlate the much sharper initial drop in the shape of the amplitude decay curve with notes that seem “dull” and more “thunky” when I play them compared to nearby notes.

I already knew the most likely reason is coupling with a resonance that matches the scale tone – but I find I understand the connection at a deeper level when I can combine multiple senses and representations.

The notes pitched around G3, G#3, A3, and A#3 all have sharper decays than nearby notes.

Intonation waveform data from A2, D3, and G3. Tracks are lined up so similar scale tones are vertically aligned.

Note: The last sample in A2 is the harmonic at the 12th fret and is a duplicate of the sample just before it which is A2 fretted at the 12th fret.

More details on the two guitars.

Both guitars have tops, bracing, and necks built for steel strings and have a 635 mm (25”) scale length. This is 5 mm longer than the 1918 Martin 1-18. The tops and backs were built with a 25 foot cylindrical radius.

I started by building one for my daughter. It has a Sitka Spruce top, spalted Norway Maple back and sides, and heat bent Hop Hornbeam bindings and rosette.

I decided very quickly I should also build one for myself and stay just a bit ahead in the process so I would make more mistakes on mine. While the form of both guitars are the same there are aspects of mine that are more unusual and experimental. The top is White Pine and the sides and back are spalted Beech. I included the ability to add masses of different weights to the interior sides of the lower bout

12th fret body join

The neck joins the body at the 12th fret which means the bridge is right in the middle of the lower bout which is only 330 mm (13”) across.

White Pine tonewood

The White Pine came from a tree about 100 years old cut down in front of the local club/bar in my tiny town. It was about 28” in diameter.

Initially I processed the split sections into panels about 600 x 200 x 6 mm, stickered them in a conditioned space at 45% relative humidity with a mild airflow. These panels reached an equilibrium weight in about three weeks. I reduced the thickness to 4 mm and squared off the ends.

I then baked one set of panels for 90 minutes and another for 270 minutes at 200 degrees in a large convection oven. The goal was to harden the resin in the pine by volatilizing the lighter components. I was not trying to dry the boards further so I included a large flat tray of water in the oven during this process.

I then created a spreadsheet implementing the methods Trevor Gore describes for characterizing panels for tops and coming up with a target thickness and predicting what the mass of the top plate will be. See: Contemporary Acoustic Guitar Design and Build: Gore & Gilet v1:p4-63.

- Measured length, width, depth, and mass for each tested panel and calculated density.

- Determined main resonant frequency for long grain, cross grain and cross-diagonal for each panel. Used a good microphone with a wide frequency response to collect data with Audacity and determined the fundamental pitch for each mode using the Spectrum Analysis feature.

- Used Gore’s formulas to calculate stiffness in GPa for the long axis, the cross-grain axis, and the twisting stiffness associated with the cross-diagonal mode.

Comparing the White Pine panels baked for 90 and 270 minutes.

| Average | 90 minutes | 270 minutes | change % |

| density (kg/m3) | 455 | 496 | 9% |

| Long-grain stiffness (GPa) | 7.19 | 10.13 | 41% |

| Cross-grain stiffness (GPa) | 1.02 | 1.30 | 27% |

| Diagonal stiffness (GPa) | 0.89 | 1.61 | 80% |

| Sound Radiation Coefficient | 8.74 | 9.10 | 4% |

| Target Thickness (mm) | 3.0 | 2.6 | -13% |

| Panel mass (grams) | 164 | 157 | -5% |

Elements of these data are a bit surprising.

All the panels came from the same section of the tree. I have no idea why the panels baked for 270 minutes got 9% denser than the panels baked for 90 minutes. Am pretty sure I also measured density before baking but can’t find that data. I do have more split pieces of the White Pine that haven’t been baked and I may try and replicate the experiment.

The Wood Database web site lists an average density for Eastern White Pine of 400 kg/m3. This is about 12% less than the panels baked for 90 minutes and 25% less for the panels baked for 270 minutes.

In any case I used a bookmatched pair of panels baked for 270 minutes for the White Pine top guitar.

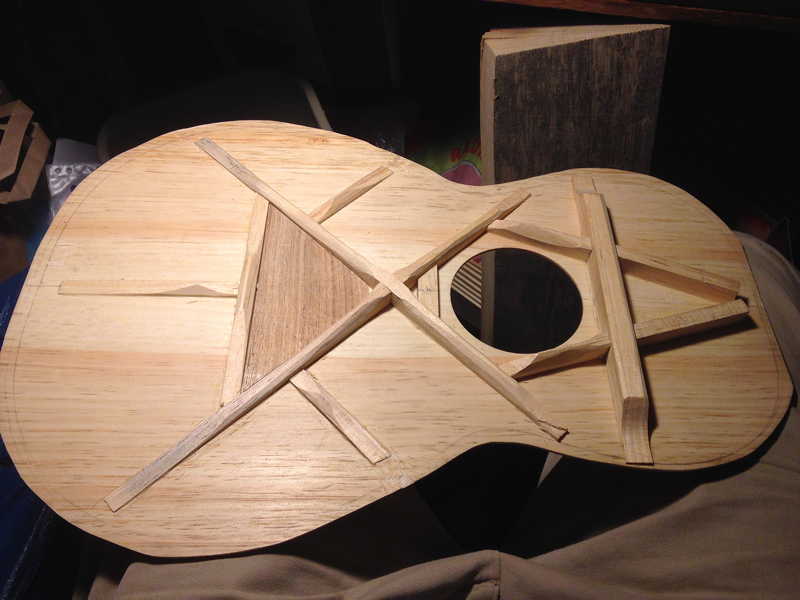

Modified X bracing

A modified X-bracing developed by John Fabel is used for the tops of the guitars. Butternut is used as a bridge plate.

Carving Braces for White Pine top.

Using Chladni patterns to complete brace shaping.

The top is placed on four foam pillars, black tea is sprinkled on the top and a sine wave is played from a speaker below the top and swept from 50 to 1000 Hz. At points when the resonances build up in the plate the dark tea leaves are bounced away from the anti-nodal sections of the plate that have larger oscillations and move towards nodal points where the oscillations are less. When enough black tea leaves migrate to the node lines the lines become easy to see. At this point the sweep is paused and the Chladni patterns for that frequency are recorded.

Shaping the braces continues until the the T(1,1)2 resonance is a smooth continuous curve and as close to the edge of the lower bout as possible. See the sixth picture below at 237 Hz.

Chladni patterns for finished White Pine top.

The other Chladni patterns recorded might be helpful later when I have a historical record of these data that can be correlated with other characteristics of completed guitars.

Finished braces and Butternut bridge plate for White Pine top.

Laminated bridges

The bridges are laminated with Butternut on the lower layer and either Beech or Black Birch on top. The grain of both pieces is running parallel to the top of the guitar to maximize the strength opposing the rotational torque from the strings tension transferred through the saddle. The bridges weigh only about 15 grams.

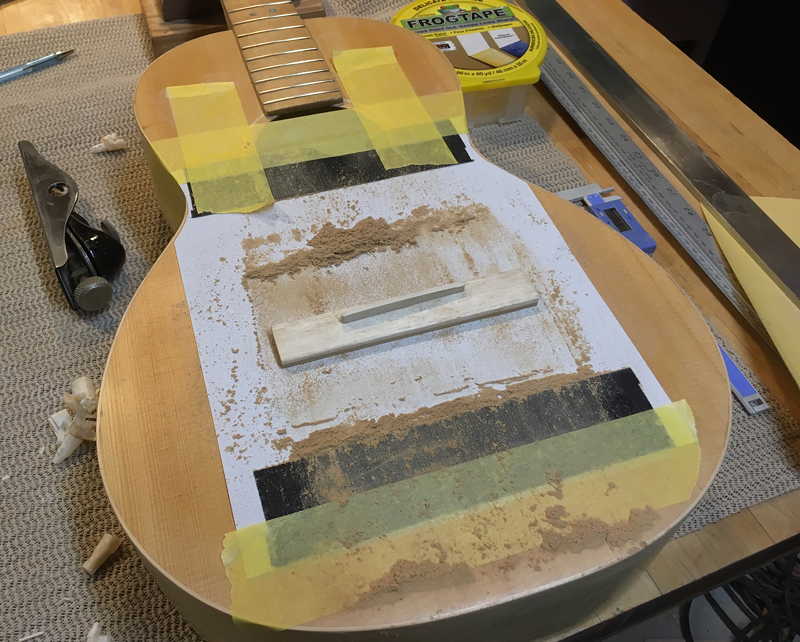

Shaping lower Butternut lamination to match radius of top.

__

Gluing laminated bridge to Sitka Spruce top using cam clamps and shaped foam cauls above and below. The foam cauls are laminated with thin plywood.

Live backs

The lower bout section of the backs of both guitars are designed as live backs with the main cross-brace scooped out in the center along with radial bracing to contribute to harmonic richness both directly and also via coupling with resonances in the top.

Radial bracing on Beech live back for White Pine guitar.

Side mass weights

On the White Pine guitar there are two sturdy small platforms attached to the sides in the interior of the lower bout just before the waist. These have 1/4-20 threaded inserts so I can experiment with attaching different steel mass weights to the sides. Attaching a mass rigidly to the sides make both the top and back plates more efficient by reflecting more of the vibrational energy back into the top and back. Another effect is a correlation between an increase in side mass and a larger oscillating area on the top and bottom plates. The larger oscillating area also means that the main resonant frequencies are lower in pitch. By changing the side mass weights the guitar can in-effect be tuned so the main resonant frequencies avoid standard scale tones.

Mounting platform for side mass weight.

Side mass weight attached.

Heat-bent multiple-strip kerfling

I enjoyed bending the sides so much that for the White Pine top guitar I decided to build the kerfling out of multiple heat-bent strips of cypress instead of the standard saw-cut kerfling. I think it ended up with sort of an art-deco look. Of course it’s incredibly strong.

Multiple strips of heat-bent kerfling glued to sides.